Note: Martin Luther King was Killed April 4, 1968. This article is a reflection of what happened in Washington DC the next day.......

washingtonpost.com

Embers From the Fires of '68

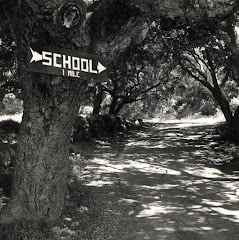

Washington at 2:30 p.m. on April 5, 1968. The Washington Monument is visible in the distance.

By Roger Wilkins

Thursday, April 3, 2008;

Late in the evening of April 5, 1968, the sky over Washington was empty except for our Air Force jet tearing north. On board was the delegation that President Lyndon Johnson had sent to Memphis before dawn that day to convey his condolences and those of the nation to Coretta Scott King and her family as they arrived to take the body of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. home to Georgia. Led by Attorney General Ramsey Clark, our group included Equal Opportunity Employment Commission Chairman Clifford Alexander, associate FBI director Cartha DeLoach and Justice Department public information chief Cliff Sessions.

There were no other planes in the sky because the Federal Aviation Administration had closed Washington's airports to commercial traffic after riots and fires had broken out in several cities. Considering the blows our country had just absorbed, the absence of regular air traffic was unremarkable, but I realized as I looked out the window that I was staring at something odd -- a dim orange glow that seemed to have a needle threading it. It brightened as we flew closer, and suddenly I realized that the "ball" was actually the glow of many fires and that the needle was the Washington Monument.

At the time, I was director of the Justice Department's Community Relations Service. Since the summer of 1965 in Los Angeles through the summer of 1967 in Detroit, I had seen violence, destruction and death that I tried to understand and to explain to people who were not black and poor and were not consigned by poverty to the worst living conditions in America. But this was different: It had been my friend Martin lying dead in Memphis, and now it was the home town of my adulthood that was burning.

That day, Mrs. King had been composed and strong -- regal, really -- in her graciousness. Others in the family party had a harder time containing their grief. We met with the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. King's best friend and colleague, and other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Two things were obvious during our visit: These people were suffering mind-numbing grief. But they had no thought of abandoning the Poor People's Campaign they had been planning to bring to the nation's capital that summer.

As the administration official designated to interact with the campaign, I had had several conversations with Martin as he altered and expanded his conception. This was a pivot from his just-ended Chicago campaign, which had become, like Napoleon's armies in the snow of a Russian winter, mired in Northern racial callousness, the ham-fisted racism of the first Mayor Daley and the general inertia of a massive urban bureaucracy. Martin decided to dig more deeply into American culture and to seek a more encompassing justice than the civil rights movement would have been able to achieve. The new campaign was to bring the widest array possible of America's poor to Washington. Young and old; red, brown, white and black, they would come to the Mall to claim the parts of the American dream that had been denied them only because they were poor.

As we neared the heart of the city, we could distinguish the long streaks of fire, especially along 14th Street NW and H Street NE. Someone near me remarked, "Looks like Dresden." As the plane wheeled and headed back toward Andrews Air Force Base, I looked down at Anacostia, the city's poorest quadrant -- where I saw no fires.

In Chicago I had once watched Martin teach nonviolence to a group of gang members in his small living room in the ghetto. The kids (frightful young thugs to most people) were infuriated because the governor had sent the Illinois National Guard into their turf to stop a riot. Martin preached until they promised to return the next day to join in one of his ghetto-uplift projects. He probably saved several lives in that post-midnight meeting. There were no journalists there -- just John Doar, the legendary assistant attorney general for civil rights, and me. Afterward, Martin invited us to join him and Coretta for coffee. We talked about the relentless, corrosive effects of poverty as the sun rose over the ghetto.

When I got home the night of April 5, 1968, I looked out my front window and was stunned, and a bit annoyed, to see National Guardsmen in the shopping center across the street in Washington's "New Southwest." In 1968, Washington was moving toward democracy in the small steps permitted by the White House and Congress. Its instruments of governance were frail and young. The poverty in far Northeast and Anacostia should have been the shame of the nation.

Today, we have a much more seasoned government: a hearty democracy and a sense of professionalism (jolted by scandal from time to time) that is a far cry from the arrangement being put into place in 1968. We have a young, energetic mayor who is not afraid to take risks. The members of the D.C. Council appear to be able and effective politicians. And in my neighborhood there is a sparkling new baseball stadium where a promising young ballclub plays.

But Anacostia, just across the river from the stadium, and far Northeast still shame the nation, as do many of our public schools. The size of the city's homeless population is heartbreaking. The level of criminal activity among our young people is appalling. Martin's death sapped the energy and the will of so many of us in the movement that the Poor People's Campaign was barely a shadow of the effort forming in his mind. Our city still feels the loss. The interracial coalition that might have been born in the summer of '68 is still some distance off. And the people in the Anacostias of this nation are still poor; some have now seen two or three generations of their families mutilated by the brutal poverty that we thought we might begin to overcome. They miss Martin very much, as do all of us whose lives and spirits he touched so profoundly.

The writer, a history professor at George Mason University, was director of the Justice Department's Community Relations Service from January 1966 to January 1969.

Thursday, April 3, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment